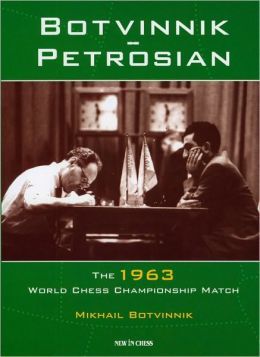

Botvinnik-Petrosian

The 1963 World Chess Championship Match

Mikhail Botvinnik

Why some World Championship matches are remembered long after they are played while others are quietly forgotten is not easily explained. Certainly the competitive drama of epic battles like Alekhine – Capablanca, Botvinnik – Bronstein, Karpov – Kortchnoi (1978) and Kasparov – Karpov (all matches), each of which went down to the wire, helps explain their enduring appeal. Likewise it never hurts to have contrasting styles and a great book dedicated to the match, as was the case for Tal – Botvinnik 1960. The media hoopla added to the drama of arguably the most famous match of them all between Fischer and Spassky, but what about the worthy matches which produced many memorable games but somehow faded into obscurity?

One that has to feature in this second group is the 1963 battle between Mikhail Botvinnik and Tigran Petrosian, which saw the “Tiger end Botvinniks almost continuous 15-year reign as World Champion. Could it be that Petrosians style was not accessible enough to the public? Did the fact that neither player produced a book on the match somehow contribute to its disappearing below the radar? Its hard to say today but we can be thankful for the recent publication of Botvinnk – Petrosian: The 1963 World Championship Match by Mikhail Botvinnik.

This is not the first book in English on this match. That honor goes to the late R.G. Wades first rate effort published not long after Petrosian was crowned World Champion. I have a copy of this hardback book complete with dust jacket which included many nice features including some excellent black and white photos, plenty of background information and the amount of time each player consumed for each move. What Wades book lacked, which Botvinnk – Petrosian: The 1963 World Championship Match has in abundance, is the insights of both Botvinnik and Petrosian. These come out in the writings of both men and their annotations to the games (Botvinnik comments on seven of the games and Petrosian on three). Petrosian is in some ways the more insightful of the two. One major point he makes is how successfully and confidently Botvinnik played in World Championship matches when he got an early lead that this was a situation that he (Petrosian) had to avoid at all costs if he hoped to win the match.

This was a unique competition. Not a single game featured 1.e4! Botvinnik, in seeding 18-years in age to his rival, became just one of three players ages 50 or over (Lasker 1923 and Kortchnoi 1981) to contest a World Championship match post Steinitz. Did Botvinnik have a hard time adjusting to a new collaborator? This match saw Semyon Furman (later to become Karpovs trainer) replacing Botvinniks long time assistant Grigory Goldberg. Botvinnk – Petrosian involved the close involvement of Botvinniks nephew Igor and understandably has a pro-Botvinnik slant to it. Goldberg does not come off well (Botvinnik would not agree to a long list of conditions) nor does Furman M.B. says he was only an opening consultant and nothing more.

Botvinnk – Petrosian: The 1963 World Championship Match is a very interesting book. Besides the comments of Botvinnik and Petrosian there are also annotations from the time by the likes of Kotov, Taimanov, Flohr, Kortchnoi and Bagirov. Petrosians fellow countrymen and number 2 in the 1999 WC Knockout, Vladimir Akobian, has annotated five games of the match specially for this volume. This book also contains previously unplayed training games between Botvinnik and Furman as well as Botvinniks final notebook started in response to a possible match with Fischer.

Strongly Recommended.