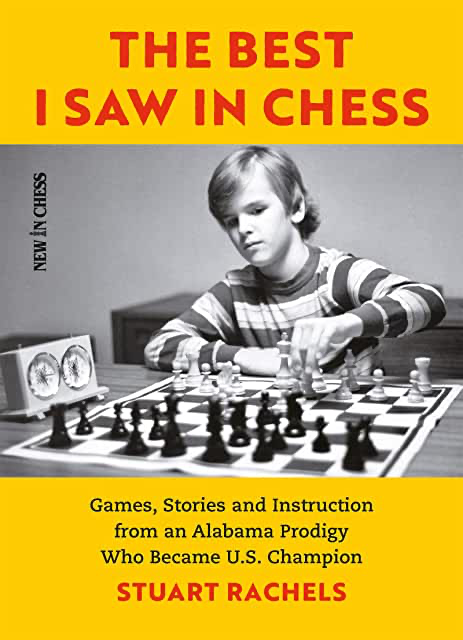

The Best I Saw in Chess

Games, Stories and Instruction from an Alabama Prodigy Who Because U.S. Champion

Stuart Rachels

The author of The Best I Saw in Chess is likely unknown to chess players under 40, but for older ones Stuart Rachels is well remembered for sharing first in the 1989 U.S. Championship, one of only two non-Grandmasters to do so in over 60 years Rachels was only twenty years old when he won the title with greater results seemingly right around the corner, but three years later he retired from the game to pursue a career in academia. Absent for the game for almost thirty years; he has returned with a combination game collection/ memoir.

He may not have been playing chess the past three decades, but it’s clear from the extensive bibliography that Rachels has not gone cold turkey. Not only has he been reading a lot, he has kept in touch with a close-knit group of friends. This includes FIDE Master David Gertler who provided the computer expertise to make sure the analysis in this book is at a level one expects in 2020.

While that is important, what the reader will really like about this book is the care with which Rachels has annotated the games. While analysis is given where needed, it’s the extensive prose commentary that will be best appreciated by the average reader when going through the 124 games and fragments on offer.

Not only the game analysis is first rate. This book is well written and accurate, as one might expect from an academician, and comes complete with detailed indices and footnotes. The only factual error I spotted in 414 pages was on page 103 where Raymond Keene is referred to as England’s first Grandmaster (Tony Miles was).

The Best I Saw in Chess is also part memoir and this is where things get a little tricky as the author is writing about events that happened thirty to forty years ago. Rachels has a terrific memory and his recollection of events known personally to this reviewer were uniformly spot on. There is no concern there.

What’s more complicated is his assessments of colleagues, many of whom he has had no contact with since his early twenties. Sammy Reshevsky, who was never noted for sportsman like behavior, and whose shortcomings in this department are well-documented, comes in for justified criticism from Rachels. Fellow Grandmaster Arnold Denker, who shared Sammy’s “sharp elbows” over the board, but was more charming off it, is praised. One wonders if the author might have changed his views assessments if he had known Denker longer.

One individual this reviewer wishes more had been written about is the late Boris Kogan (1940-1993). Rachels earned the USCF master title before he turned twelve (at the time a record) while living in a chess desert (Alabama), so he was unquestionably a big talent. That said he mentions in the preface he would never have become the chess player he did, without Kogan’s help. Their relationship started when Rachels was 12, possibly a little earlier, as the author writes he progressed from 2100 to 2600 USCF under Kogan’s tutelage. At all the key moments Kogan was there to help him. This included the 1989 U.S. Championships where his adjournment analysis resulted in two extra half points, turning a good result into something special.

Rachels, who was always a terrific calculator with a strong feel for the initiative, credits Kogan with teaching him the finer points about endgames and positional chess, but it would have been interesting to hear more about how they worked together.

Kogan, who was a modest man as Rachels points out, had an unusual chess career. If online sources are to be believed, he won the 1956 and 1957 Soviet Junior Championships, which would have been a huge accomplishment. Soviet junior chess was not at its best in the mid-1950s, the losses of the Second World War still being felt, but to win the title back to back and at such an early age, would have been an indicative of great potential.

It was not to be. Everything points to Kogan transitioning at an early age from player to coach and what a trainer he was. Rachels mentions Leonid Stein and Alexander Beliavsky as two of the players he worked with.

Kogan didn’t completely stop playing completely (he was second in the 1971 Ukrainian Championship), but clearly his personal ambitions had to take a back seat. This changed when he, his wife and young son emigrated to the United States around 1980. All of a sudden, he had to adjust to a completely different situation where the government didn’t support chess.

To support his family, Kogan, who was already over 40, had to not only teach but also play. He adapted well. Returning to regular tournament competition he played in six US Championships between 1981 and 1987, finishing with plus scores in 1984 and 1985. His rating of 2500 FIDE on the January 1985 rating list might not seem exceptional now, but at the time it made him the 92nd rated player in the world. Clearly, Kogan deserved to be a Grandmaster and he would have had he not succumbed to colon cancer in his early 50s.

One can imagine that for Kogan, who worked primarily with adult club-level players in Atlanta, it must have been a great pleasure to have worked with such a promising young player as Stuart, even if there were logistical difficulties (the Rachel’s family living 150 miles away in Birmingham). There were ups and downs and Rachels doesn’t just cover the high points. He writes about losing back to back games to Dreev and Ivanchuk in the 1984 World-Under 16 Championship and the embarrassment Kogan felt, not so much at the results as Stuart’s play in the second game where he lost like a child. Rachels was only 14 at time and only later could he appreciate the professional embarrassment Kogan felt, feeling humiliated in front of the Soviets coaches he knew from the old days.

The Best I Saw in Chess is a book that deserves a wide audience. Players from 1600 on up will find it both a good read that is full of instructive commentary.